The Surprising Formula Every International Investor Must Know

Mexico and Brazil had a big problem several decades ago.

They had a small but very wealthy elite class and a massive underclass. The middle class in these countries was relatively small, leading to low levels of domestic consumption.

Since then, a set of far-sighted government policies has helped to create thriving middle classes in these countries, and it’s no coincidence that their stock markets have surged: Brazil’s BOVESPA market index has surged 500% in the past decade, while Mexico’s stock market has risen a heady 600%. As a result, in both countries, exciting and rewarding investments await the investor.

Economists can even quantify the middle-class gains in these countries using a little-known ratio called the Gini coefficient. Developed by an Italian mathematician a century ago, it’s a formula that assigns a value of zero to a society where the wealth is spread amongst all citizens. Very complex math that goes into determining wealth distribution — suffice it to say it’s far more complex than simply measuring the wealth of the top and bottom of the population.The index applies a theoretical value of 100 to any country where all of the wealth is held by one person. Of course, no country has hit that mark, but South Africa’s 63 rating — the highest of any major economy in the world according the World Bank — is fairly alarming.

Wondering how the United States measures up? As of 2010, our Gini coefficient index stood at 40.8. That’s right in the middle of the global rankings, according to the World Bank’s methodology. Other groups that track the Gini coefficient have noted that the U.S. score has worsened in recent years. Historically and — and anecdotally — there is evidence that much of the wealth created in the United States in the past two decades has been accrued by America’s most wealthy 10%. A rise in the Gini coefficient bears that out.#-ad_banner-#

Should this be cause for concern? On the face of it, unfettered capitalism has built a pretty strong track record in the past half century as all members of society in the United States, Western Europe and Japan have seen rising living standards across the board.

Yet a key concern, beyond the basic notion of fairness, is the erosion of a broad base of taxpayers that can support a government’s revenue base. Inflation-adjusted income for many Americans has been stagnant for two decades. Had their incomes risen in tandem with those of the top earners, we may not be facing a budget crisis right now. Regardless of your politics, it seems reasonable for any country to strive for a robust middle class.

In some countries, governments have worked assiduously to ensure that almost every citizen is within the reach of a middle-class lifestyle. Take Norway. That country has reaped hundreds of billions in profits from its lucrative North Sea oil fields. The Norwegian government has used those earnings to shore up a wide range of social services, from education to retirement to job training.

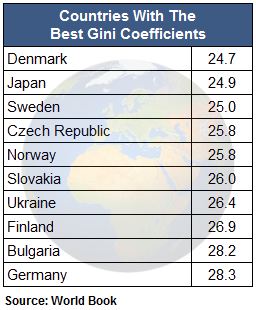

As a result, Norway had one of the world’s lowest Gini coefficients in the world in 2008: at just 25.8, it had the fifth best score in the world.

As a result, Norway had one of the world’s lowest Gini coefficients in the world in 2008: at just 25.8, it had the fifth best score in the world.

The first table here shows how it compares to the countries with the lowest Gini coefficients in the world.

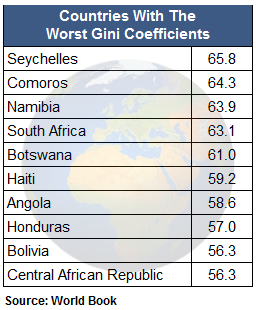

At the other end of the spectrum, Africa is home to countries that have massive wealth inequality. South Africa’s Gini coefficient has actually worsened in the post-Apartheid era.

In our hemisphere, Bolivia, Paraguay, Honduras, Guatemala and Colombia have high Gini coefficients.

On the two-nation island of Hispaniola, Haiti measures 59.2, while the Dominican Republic scores at 48.2, which partially explains the ongoing eastward migration of Haitians into the Dominican Republic.

The countries with the highest Gini ratios often also have the most political turmoil. For those of us in the West who are accustomed to a broad-based middle class, travel to such countries can take an emotional toll as you come up against entrenched poverty. (I still have many unpleasant memories of childhood trips to Haiti.)

But a poor Gini score doesn’t mean that a country is a bad investment arena. It’s the direction of the Gini score that counts, as Mexico and Brazil can attest.

Action to Take –> As an investor, seek a country’s Gini ratio as you research the prospects for various emerging markets. Countries like Brazil and Mexico, which historically had very high Gini ratios, have made sharp improvements in this area and, as a result, have delivered solid investment returns in recent years.

This article originally appeared on InvestingAnswers.com:

The Surprising Formula Every International Investor Must Know